Cinema's Silly Little Archetypes

Manic Pixie Dream Girls, Stale White Wonderbread Boys, + Ratatouille Grumps

The Manic Pixie Dream Girl

In man’s feeble attempt to understand women they like, they created the Manic Pixie Dream Girl Archetype.

In 2007, film critic Nathan Rabin published his fateful pan of Cameron Crowe’s Elizabethtown, in which he coined the phrase “Manic Pixie Dream Girl,” describing Kirsten Dunst’s quirky, unbelievable character.

In the years to come, Rabin would publicly regret coining the term: While the “MPDG” was meant to criticize male filmmakers for writing one-dimensional female characters that only exist to make men’s lives better, the label was soon overused and misapplied to describe any unique, otherwordly, “pixie”-like female character.

So, why is the Manic Pixie Dream Girl still a thing?

If men, on average, are objectively worse than women at matters of the heart, doesn’t it stand to reason that they would have a hard time understanding the women they love? Can we really expect men — of all people — to create art that accurately and beautifully illustrates women?

(Of course, I’m making sweeping generalizations about men, but that’s what a sweeping generalization of women calls for.)

Evidently, some men believe the Manic Pixie Dream Girl is flattering. A fantasy, single-faceted dream girl falls from the sky in a man’s moment of need. The only problems she possesses come in the form of adorable quirks, and she’s independent enough to only need from a man whatever he can give (read: needless). Doesn’t that make women seem great?

In my humble opinion, this is how young men often see their love interests, not because women fit this stereotype, but because men have not taken the time and effort to fully get to know their love interest as a human.

In real life, in time, men either eventually come to understand women as full persons, or they do not and the relationship suffers. If the Manic Pixie Dream Girl movies were to carry on past their epilogues, I suspect we’d see this play out. But these types of films are escapist in nature, and who wants to ruin the fantasy?

It’s worth noting that the label of “Manic Pixie Dream Girl” is too often applied to any unique and quirky female character. Kate Winslet’s Clementine in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is a great example of this: Internet listicles label her as a MPDG even though she is revealed to be quite the multifaceted character with her own will, wants, and needs. Confused? This is where the Stale White Wonderbread Boy comes in…

The Stale White Wonderbread Boy

Nearly twenty years after the phrase “Manic Pixie Dream Girl” was first coined, Final Girl Diary coined the term “Stale White Wonderbread Boy” to describe the male characters that play opposite cinema’s fantasy ladies.

Stale White Wonderbread Boys are the observers of the Manic Pixie Dream Girls. One cannot exist without the other. By their very nature, these men cast a male gaze characterized by its ineptitude.

As Final Girl writes, Stale White Wonderbread Boys are “often boring, unimpressive, average boys played by white male actors, who are typically normal looking enough so as to retain a level of non-threatening relatability to the men watching… Their purpose is to gaze, not to be perceived.”

I particularly enjoyed that Final Girl Diary makes the distinction between Manic Pixie Dream Girls and Femme Fatales in their piece, noting:

“[The] Femme Fatale archetype is not reliant on a specific male stock character to be perceiving her. Though there are common male stock characters that will likely appear, such as the detective, these male stock characters are not reliant to make the Femme Fatale a Femme Fatale, nor do these detectives need to be the center of the story in order to perceive her through their very specific gaze.”

Femme Fatales (such as Jennifer’s Body, Gone Girl, Jackie Brown, and Double Indemnity) are just as fascinating and appealing to men, but they appear in movies with all sorts of men, not just Stale White Wonderbread Boys.

No, these unimpressive male leads are destined for their shallow perceptions of Manic Pixie Dream Girls, and nothing more.

Some directors have attempted to turn these tropes on their head. I would argue Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s Tom in 500 Days of Summer becomes a reformed Stale White Wonderbread Boy — a “Multigrain Loaf Young Man”, if you will — by the end of the film.

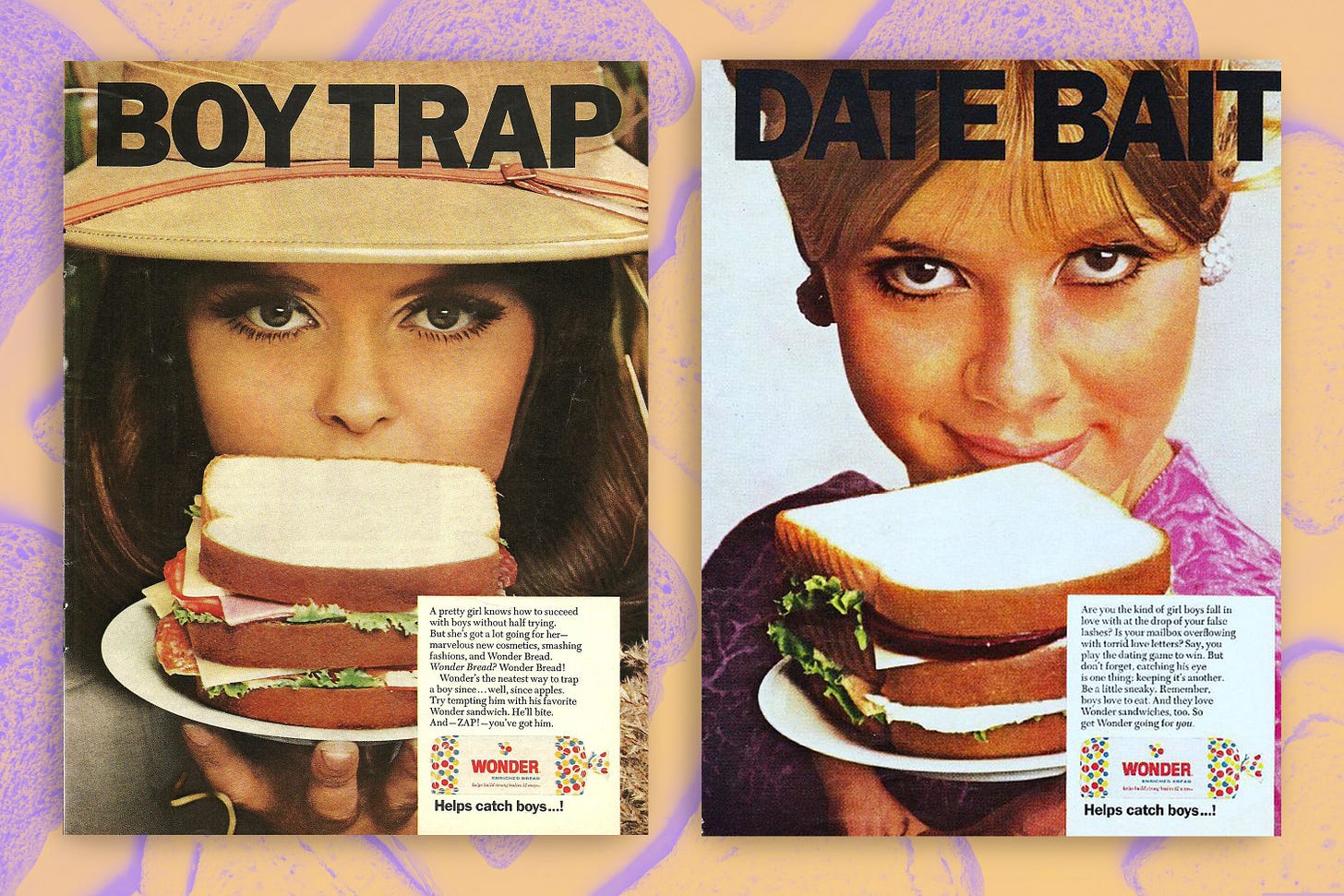

Interestingly, I found some vintage Wonder Bread print advertisements (pictured above) circa the 1960s advertising their product as a proverbial milkshake to bring all the boys to the yard, so to speak. It’s almost as if Wonder Bread themselves invented the Manic Pixie Dream Girl back in 1968.

Despite Nathan Rabin’s regretful warnings, the discovery of the Stale White Wonderbread Boy archetype has inspired me to come up with a few terms for other archetypes I’ve noticed in modern cinema…

The Murderous Licorice Teenage Girl

A few weeks ago, I wrote about how candy and teenage girl violence go hand-in-hand in Hollywood. The archetype has its roots in Michael Lehmann’s Heathers (1988), often considered a reaction to the feel-good young adult films of John Hughes’s 80s.

Over the years, candy-colored teenage girl murder arguably became a black comedy subgenre. Even when candy is not on screen, bright and pastel candy-like colors are almost always used.

From there, the trope snowballed through the 1990s, experiencing resurgences in the late 2000s and mid-2010s, recently culminating again in works like Ryan Murphy’s Scream Queens. You can read more about the Murderous Licorice Teenage Girls by clicking the link below:

I thought about dubbing this character with “Bubblegum,” but given Heathers features a licorice-loving Winona Ryder, the title of Murderous Licorice Teenage Girl feels the most appropriate here.

The Reformed Little Fantasy Freak

We watched as Harry Potter’s Daniel Radcliffe took on projects like Guns Akimbo, Swiss Army Man, and Weird: The Al Yankovic Story.

We looked the other way when Orlando Bloom starred in films like Tour De Pharmacy and the aforementioned Elizabethtown.

And let’s not forget Elijah Wood’s appearances in Spy Kids 3-D, Grand Piano, and I Don't Feel at Home in This World Anymore.

If you were a strapping young gentleman who starred in Lord of the Rings or other blockbuster franchise fantasy films, you will meet a fork in the road: Turn left, and you will continue to star in fantasy / sci-fi flicks well into old age.

But turn right? Oh boy, you are in for a treat. Your career path will go the way of the many Radcliffes and Woods before you. Indeed, the Reformed Little Fantasy Freak offers roles ready to welcome you with open arms. We all know you were attracted to fantasy roles for their freaky-ness. Now, it’s time to embrace your inner freak even more, bringing him into more daring, modern settings and independent cinema.

For those of us at home, there are few things that can jolt you out of a rut more than viewing a Reformed Little Fantasy Freak film. Your brain won’t know quite what to make of seeing your favorite hobbit or wizard using a cell phone and firing guns. And isn’t it best to keep your noggin on its toes?

While most Reformed Little Fantasy Freaks are men, I am pleased to report I believe the one and only Emily Browning fits into this category. From Lemony Snicket’s Series of Unfortunate Events, Sleeping Beauty, and Sucker Punch to American Gods, it’s safe to say she’s embraced the little freak within, beyond conventional “fantasy” confines.

The Flavored Lip Gloss Besties

For many women, their idea of success might include a man or material items, but always involves healing and honoring their inner child. Films that portray this journey are often lumped into the “romcom” genre, but their stories reach beyond the bounds of traditional romantic comedy.

Flavored lip glosses — whether they be cherry, raspberry, or Skittles™️ flavored — are often thought of products only young girls should engage with. I believe Uptown Girls’s Molly Gunn or 13 Going On 30’s Jenna Rink would use these products any day they felt like it, well into their 90s.

If a film features a coming-of-age story with a girl becoming a woman, perhaps healing her inner child, and you can picture her putting on some lipsmackers well into old age, it’s safe to say she’s Flavored Lip Gloss Bestie.

The Comes-Out-Of-Hiatus Guy

The lights dim. Action movie trailer after action movie trailer plays. Finally, after twenty animated production company logo cards, a Hollywood movie star appears on screen. They’re playing a family man, or a secluded lone wolf — a regular guy just looking to be normal. Until one day, five minutes into the movie, he gets a knock at the door, a text, perhaps a message slipped under the door. His old bosses, they need him. One last job. Can he do it?

Whether he’s a good guy or a bad guy, the action movie you’re watching follows a Comes Out of Hiatus Guy. Arguably the perfect action movie trope, Comes Out of Hiatus Guys — think Liam Neeson in Taken — can take a regular-schmegular plot and turn it into a cultural touchstone beloved by the whole family. Everyone loves a comeback fantasy.

Speaking of, if you haven’t checked out Boy Movies by allison picurro, it’s a must-subscribe.

The Ratatouille Grump

Again, I’ve written about the “Ratatouille Moment” already on Film Flavor: Coined by Kimberly Woo, the term refers to that moment when something warms the heart of a cold critic, causing them to see the world in a new light.

Paul Giamatti in The Holdovers, Anton Ego in Ratatouille, and every iteration of A Christmas Carol’s Ebenezer Scrooge all fall under the Ratatouille Moment Grump archetype.

It’s worth noting that I believe famed film directors Ingmar Bergman and Andrei Tarkovsky were Ratatouille Grumps in real life, experienced the foretold transformations, and made Wild Strawberries and The Mirror respectively in their attempt to process their feelings.

Your Cinematic Archetypes + Tropes

Have you noticed a pattern of underestimated grandmas?

Town drunks with a change of heart?

You’re in the right place! Share the character tropes you’ve spotted in the comments below, and help educated the Film Flavor audience.

Our Collective Desire to Label Trends and Archetypes

See — Isn’t coming up with labels and archetypes fun?

In the social media fashion space, many of us have watched as seashells and leopard prints have experienced quite minor boosts in popularity, only to be packaged into a label — “Coastal Grandmother” or “Mob Wife Aesthetic” — and skyrocket into mainstream fashion. Once a name for a loosely defined cultural phenomenon is defined, it becomes easier to Google, easier to discover, and easier to consume.

Nathan Rabin gave birth to the Manic Pixie Dream Girl label, and now he pleads with us to heed his warning: “By giving an idea a name and a fuzzy definition,” Rabin writes in Salon, “you apparently also give it power. And in my case, that power spun out of control.”

Nathan’s sheepish apology reminded me of the recent Hulu1 documentary Brats chronicling the 1980s movie star “Brat Pack” and their eventual confrontation with the journalist who coined the term.

Do we think Kirsten Dunst would ask Nathan Rabin to apologize to her for the Manic Pixie Dream Girl label, if they ever met? Or would she simply thank him, for all press is good press?

A Quick Note of Trivia on Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

Kate Winslet’s Clementine, an oft-accused Manic Pixie Dream Girl (though as we discussed above, not so.) Still, there are some fun archetypal connections: Kirsten Dunst, once a Murderous Licorice Teenage Girl and the original Manic Pixie Dream Girl, and Elijah Wood, a certified Reformed Little Fantasy Freak, take on the B plot. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind has much ado regarding silly little cinematic archetypes.

Disclaimer: Film Flavor is a newsletter written for entertainment purposes only. While I do my best to write meaningful posts with good intentions and cite sources when I have the bandwidth, I do not have the capacity nor the expertise to fact-check research as a trained professional journalist would. Despite my best efforts, the Film Flavor newsletter may contain omissions, errors, or mistakes and cannot be relied upon for accuracy or correctness. Additionally, I am not a chef, doctor, nutritionist, or food professional, and it is the responsibility of the reader to consult qualified professionals and use good judgement to decide whether the ingredients, foods, drinks, recipes, and cooking instructions mentioned within Film Flavor are safe to use, follow, or consume. The Film Flavor newsletter does not contain any professional advice or guidance and its contents should not be considered as such. Read the full Film Flavor disclaimer on the Film Flavor About Page, here. Thank you!

In Case You Missed It…

Further Reading…

Want more movie snacks? The #1 way you can support Film Flavor is by subscribing and sharing this post with friends via the buttons below!

Leave a Comment and let me know: Do you have any film character archetypes of your own?

With gratitude,

Correction: A previous version of this article stated Brats belonged to another streamer. It is, in fact, available to stream on Hulu, here.

Winona in Heathers is definitely a root for so many cinematic alt-girls stuck in the limbo between good girl and bad girl (see, also Alabama from True Romance)

[also, I believe Brats is a Hulu doc, not Netflix]

I recently wrote a piece about the sports-business micro-genre and in it, as well as while researching for it, I discovered the pattern of sports managers/coaches having: a) a failure that hangs over them (either career or romantic) b) a desire for innovation, to change something about the sports industry and c) a poor relationship with a colleague.

So I guess that's a... Dejected Genius Sports Coach? Open to suggestions 😭